Discovering the Musical Standards of Your Program

All across the educational landscape today, performing arts educators are being asked by administrators how students in band, choir, and orchestra are graded. For some time, teachers in other disciplines have been asked the same question. Now, administrators are knocking on the door of the music rehearsal room to find out how their music directors grade music students in their ensembles. An entire industry has grown up around the topic of assessment, but the solutions that have come forth from “assessment gurus” around the country, have failed to measure what music directors teach in their classrooms.

We Teach Performance

As school opens this fall, teachers gather for orientation to start their year. Schools starting new initiatives to “grade better” may present plans to revise a school’s method of assessing individual students for student growth, teacher accountability, or methods aligned with “current thinking".

For the most part, the methods that a music department is asked to deploy to “improve how we grade,” are mere “exercises” to music directors. While the concepts are valid, the tools used in non-performing subjects (math, science, history), cannot measure what we teach in a performing arts class. So, to meet teacher requirements, we go through the exercise of writing objectives, formulating learning outcomes, creating written tests, or requiring outside concert attendance that do very little to assess how our students perform. In short, we live in a different assessment world than those who teach in a traditional classroom. But we’ve yet to come up with a solid explanation of why we are different and, more significantly, how we are assessing individual students.

And yet, performing arts educators assess students more than any other teacher in the school building. It’s how we teach. Every time we cut off the ensemble, show students the correct fingering, or entice them to express their music as the composer intended, we are assessing. And the student knows it. No student is surprised by the “questions on our tests.” And they know many of the answers because they audibly hear other students who are playing the part correctly. Essentially, the “right answer” is present at all times—an aural “cheat sheet,” if you will. But the answer is not just in “learning it ” but in “performing it.” In fact, it is not fully “learned ” until it is “performed ”. Students are assessed by the conductor , an expression from the podium, or, as the kids will say, “the look” when things go amiss. In music performance, the test is performing the answer rather than writing it down.

Widening Your Assessment Scale

The key is to use a scale of measurement wide enough to encompass the vast range of differences we already perceive between the top musician in a section and the musician with the least amount of ability. Every music educator, regardless of how much they assess, knows how their students rank as performers. They know who can handle a more difficult musical passage versus the student who needs a more simple part to perform. They know what music to pick for concerts, based on the strengths and weaknesses of their group. Thus, our knowledge of how kids play is already present. We can differentiate wide differences between our 5th grade beginners and seniors. Therefore, we must use a wider range than zero to 100, or A thru F.

Your system of assessing music performance must be able to distinguish between one player and all others playing the same instrument—with no ties. It requires a numerical scale beyond the 100 points commonly used. In addition to ranking each student, scoring systems must show appropriate distance between each performer, also. This differentiation shows how much better Rebecca is than John. It is only by using this process that you can learn your standard. It does not require revealing your ranking to your students unless you choose to do so. But good teaching would call for individual students to know how they rank against the standard of the group—either by grade or by the requirements needed to perform in each ensemble.

To begin with, give yourself enough numbers to place every student’s ability on a scale. Use those extra numbers to put the proper distance between each student so ranking and degree of difference is measured. Use those numbers for each category placed on a contest-like sheet (with tone, intonation, musical expression, rhythm, etc.). You will find that using just one decimal within each category (3.5 out of 4 for each caption–tone, for example) will result in a total score (adding up all categories) that will give you 3 numbers after the decimal point, creating separation. Do not attempt to rank captions like “tone.” It’s not a tone contest, so they can tie. Finally, use the scale to rank instruments or voices separately (i.e., rank clarinets with clarinets).

You will find that the key to all this is knowing your standard for every instrument or voice. All clarinets are measured against the standard within your program for clarinetists. The key point is “within your program.” We all know who the finest player is (on any given instrument) during our time at any given school. That student is the standard. Place any number on it (10.0, 7.0, etc.). Then measure all other players against that top musician on that specific instrument with the appropriate number of points between each that reflects the ability-distance.

If someone comes into an audition and outplays the best you’ve ever heard at your school, they become the new standard. This is why many who use this system, use numbers that give “room at the top.” High school students and parents are told that the 10.0 range is a professional level, and the 8.0 and 9.0 range is a music major in college. By using these numbers, getting into a top wind ensemble at the high school level might require a 7.0 or higher. And a 7.0 or higher would be required to get an “A” on a playing test once in that group.

Finding Your School's Standard

Which brings me to the matter of using this system of numbers to determine grades. If your school is a small school with one band and one choir, you can use grade level numbers such as 9.0 or higher for freshmen, 12.0 or higher for seniors (i.e., 9th and 12th grade). A senior, expected to meet the standard of a senior level performer on his or her instrument, must score 12.0 or higher. If they play an assessment and score a 10.5 based on your scale for that instrument, their average score is 87.5% (12 into 10.5). What 87.5% equates to a school’s grading system will be different for every school. But using this system allows a senior to be measured against senior standards and a freshman against freshman standards. It gives you all you need to explain how a senior trumpet player might get a “B” in band and his kid brother who plays trumpet as a freshman gets an “A.” But if your school has multiple ensembles open to students of any grade level, the ensemble method works better.

Educators will find that by using a scale that is wide enough to differentiate between every player, their ability to assess will dramatically improve. By using a comparison to the standard-setting player within each section (past or present) your program standard will start to become clear. And if more than one music educator teaches in your school, they should all do assessments during the year on all instruments. That becomes the first step to finding differences and inconsistencies among the music educators in your program and teaches them the program’s standard. Finding your standards requires ranking based on the best you’ve ever heard in your school, not the best you’ve ever heard. This is extremely helpful for young teachers who are still learning the abilities of young students.

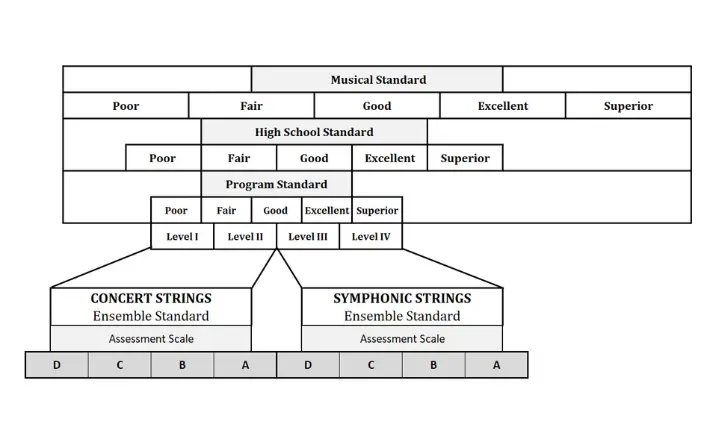

Below is an example framework to help music and other fine arts educators better visualize how their musical standard can potentially map to high school and program standards.

As your groups improve, you naturally expand the literature you perform. This means that a top performer must be ranked against the demands of the music you were playing at the time. A new standard is always set in the context of the music we perform. It is the other overriding reason why we must assess differently than the regular classroom. Our course content is never static and must be part of our standard setting process each time we increase the demands on our students and make our performing arts groups better.

Check Out Our Free Teacher Resources

Liking what you read here? Explore other helpful handouts, posters, and guides.